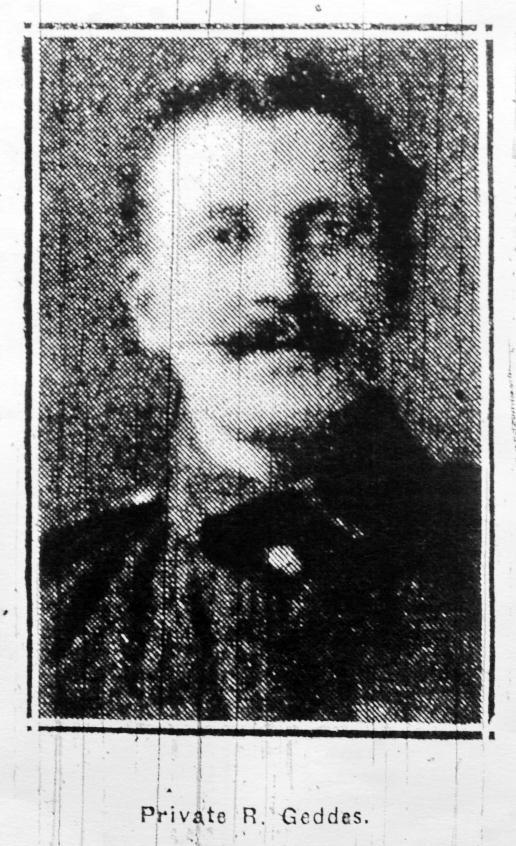

THE Great War was only two months old when Private Robert Geddes, who lived in Cherry Tree returned home wounded.

Despite his injuries, and the fact he considered himself lucky to be alive, he later re-enlisted, only to be killed on the Somme in 1916.

He served with the 8th Battalion, the Seaforth Highlanders, which fought the war in its regimental Scottish kilts – unfortunately no photographs of his have survived.

Robert was 30, married to Martha and had one son, also Robert, and prior to the war he had been a conductor on the corporation tramways.

It is believed he was killed while tending an injured soldier and was buried where he fell — as he has no known grave his name stands on the Thiepval Memorial, and is also on the roll of honour at St Francis Church, Feniscowles.

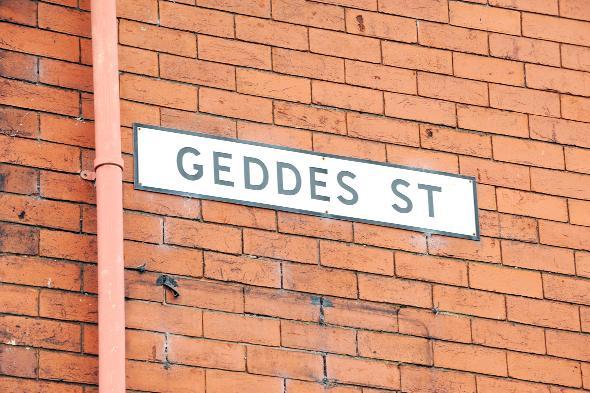

Geddes Street in Cherry Tree is named after him and his family. As he recovered from his injuries at home in Granville Street, Robert gave a graphic account of his experiences during the first few weeks of fighting.

His niece Sandra Eastham, of Blackburn has been researching her uncle and this is what he told the local newspaper in October 1914.

Our battalion left headquarters on August 6 and after a fortnight’s training, we embarked to France and landed on August 23, immediately travelling to within 800 yards of the enemy.

Trenches were prepared before the regiment visited a barn for food, 900 men enjoying tea, tinned meat and biscuits.

Suddenly we were startled by German shells, the enemy had made a surprise move and three of our number were killed and 20 others wounded.

We quickly ran over ploughed beet fields back to the trenches and we kept up a continuous barrage from 3.30pm on Tuesday until 4am on Wednesday.

It was incessant and my first baptism of fire; I was rather nervous. Overhead there was a German airship, indicating the position of the British troops, to their gunners, but we had fair warning — the shells could be heard fizzing through the air from their guns, nearly a mile away.

There was time to duck and men would shout ‘look out, there’s another telegram coming’.

I had fired 100 rounds when the order to retire came in the early morning and we marched for 30 miles – we were supposed to have a halt of 10 minutes each hour, but we were lucky to get 10 minutes every three hours.

Our retreat was in good order, without too many losses.

On our way we came across the East Lancashires with their arms piled up in the middle of a village, the Germans not being expected. But within a quarter of an hour, a strong contingent of the enemy arrived, with 14 Maxim guns and the East Lancashires suffered very heavily.

The trenches were occupied from 7am until 7pm and the engagement was marked by much bravery in the heart of the British troops. The regimental convoy had been captured so there was therefore no rations and we had to make do with fruit given us by the French peasants and turnips we plucked from the fields on our march.

The French were expected at 6am but their reinforcements did not come until 2.30pm and in the meantime a small British force kept three German army corps at bay. The French attacked the right flank, so the Germans left wing swung over a ridge within range of the British artillery and from the trenches I saw them mown down like corn before a scythe.

It was part of the plan that soldiers should retire, but the British were eager for an attack.

As the retreat did start ‘Packy’ McFarline was struck under the ear, the bullet exiting from his mouth, yet he still had the courage to shout to his comrades ‘stick it, boys. I’m all right’.

The wounded were made as comfortable as possible behind haystacks, but they had to be left in the open overnight. The order to retire by half platoons was carried out as shells dropped front, rear and centre and the regiment lost 100 killed or wounded out of 1200 men.

The retirement continued for 17 miles and the men had only been in their sleeping quarters for 90 minutes when the alarm was raised. The enemy were close and to escape the danger, another fast march of 37 miles became necessary. We were on the move for about a fortnight with an occasional brush with the enemy here and there.

The British soldiers were treated splendidly by the peasants who were kind and generous and the troops returned this kindness by giving refugees a lift whenever possible, carrying children and pushing prams when necessary.

it was a pathetic spectacle to see old people fleeing for their lives and to note the sorry plight of the womenfolk. Many of their homes had been ruined by shot and shell before their eyes.

The following week’s march was hard in the extreme; constant movements had disorganised the transports and rations were scarce and everyone shared cigarettes and food.

Everyone was in good spirits despite coming under fire in the trenches, the Dublin and Irish Fusiliers were singing ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary, while the Highland regiments replied with songs of bonny Scotland.

During the whole time, the men had never had the clothing off their backs, but we were fortunate in the district of the Compiegne to find lots of fruit in the orchards to eat.

It was around then that Robert was struck in the left leg by piece of shell, while another piece went through his jacket and a third struck his water bottle. He said: “I managed to struggle along with the rest of the regiment, but when the order to retire was given I could not keep up the pace and soon fell behind.

“After much weary tramping, I came to an encampment on the edge of the wood and was challenged by a sentry; fearing I had fallen into enemy hands I charged with my rifle. Then I noticed the sentry’s blue uniform and knew I was among friends; it was a French encampment, I shouted the few words I could remember and a soldier ran out and, noticing my kilt, carried me to their quarters.

“An officer gave me food and one of the men his bed of straw and the following day I was sent to the ambulance train to Paris and came home.”

While crossing the Channel, Robert made friends with German prisoners of war; and while he described the officers as cruelly disposed, the men, he believed, were only fighting half heartedly, as it was their duty. They also told him how they captured a sergeant and nine men from the East Lancashires, dressed their wounds, gave them milk and chocolate, placed Red Cross bandages on their arms and sent them back into the English ranks.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article