AS councils across England and Wales hurriedly move to examine their statues and memorials for links to slavery and plantation owners, Bolton’s own links to the historic trade in human beings is coming under the spotlight.

Hundreds of petitions have been started on the website Change.org to replace statues and signs of slave traders, colonialists and imperialists since the statue of Edward Colston was torn down in Bristol on Sunday.

The petitions come amidst protests around the world for the Black Lives Matter movement and justice for George Floyd. A viral petition for Justice for George Floyd has amassed more than 16million signatures, making it the biggest petition in history.

During the late 1700s and early 1800s, Bolton became a thriving manufacturing town with its growth mainly due to its extensive involvement in the processing of cotton much of which was produced by slaves in the Caribbean.

Bolton’s continued investment in the Caribbean slavery system was mainly through two families: the McConnels and the Kennedys who owned plantations in Barbados and Jamaica.

But while Bolton’s manufacturers and its population undoubtedly profited from transatlantic slavery, compared with many other UK towns and cities there was unease with the town’s links to the slave trade and following the passing of a law to end the trade by the British in March 1807, agitation to end slavery grew. In 1820 many of the emancipated slaves from the colonies who were now in Bolton spoke out against the poor conditions that existed in slavery and that year a petition was drawn up calling for the total abolition of slavery in the British colonies.

Former Mayor of Bolton Cllr Frank White, who has studied the period, said: “Bolton textile workers refused to work with slave-picked cotton during the American Civil War so much so that some mills closed.

“The workers wrote in support to Abraham Lincoln and he wrote back to them thanking them for their help and recognising they suffered hardship.

“The Bank Street Unitarians in Bolton were also very heavily involved in supporting the abolition of slavery.”

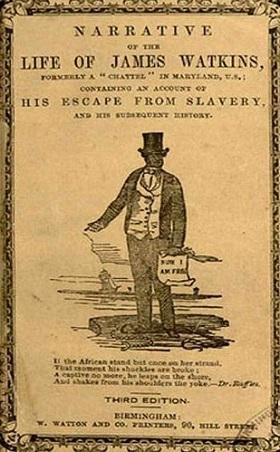

Much of the credit for the town’s opposition lies with fugitive slave James Watkins, who lectured at meetings in the Bolton and Westhoughton areas and lived in the town for a few years.

Watkins visited local mill workers to petition their support for the anti-slavery movement, emphasising the connection between the cotton industry and slavery and telling rapt audiences how he escaped, after many attempts, from his Maryland plantation.

Today there remains a plaster frieze including a depiction of a man, assumed to be Watkins, over a shop front in Market Street, Westhoughton, which is now the Provenance Food Hall restaurant.

“Watkins and a number other fugitive slaves spoke in Bolton,” added historian Laurence Westgaph. “Unlike Liverpool, the workers in the cotton towns showed much solidarity with the runaways.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel