Lancashire Police have slashed the length of time it takes to gather evidence from digital devices – after the average wait for detectives investigating cases involving computers and mobile phones topped two years.

The explosion in personal technology over the last decade had left officers facing ever-growing delays to get results from the force’s digital management investigations unit (DMIU).

The most serious offences – such as murder and rape – were always prioritised and dealt with in days rather than years. But more routine crime – much of which now leaves a digital footprint that could hold vital evidence – was getting trapped in a lengthening queue of tech which was waiting to be examined.

The Local Democracy Reportign Service can reveal that the workload of the specialist unit reached a peak of 400 cases in April 2017 – most of which required analysis of multiple devices.

The result was that the wait for the average job to be completed hit just over 24 months.

Adam Koral, who had recently become manager of the DMIU, says “it doesn’t seem real” when he reflects on the digital backlog which the department was facing.

“Other investigative opportunities may have been lost during that time – things that come out of a digital examination like email addresses, social media accounts or even just people’s names and phone numbers,” Adam explains.

“The trail can go cold quite easily.”

The logjam was the result of a rapid growth in the number of devices which could be seized during an investigation – and their expanding capacities.

“I remember us being amazed when we got a hard drive that would hold 10 gigabytes of data – everybody gathered around to read the label,” recalls Tony Carter, who established the DMIU back in 2001 and is now the force’s digital forensic gatekeeper.

“Now you can carry a terabyte of data [a hundred times as much] in your pocket without even realising it, on just one or two devices.

“Plus, we never throw technology away – everybody has got every phone they have ever owned just in case they need it one day.”

The stultifying pressure of searching every piece of kit that was bagged up and brought to them as potential evidence sparked a radical rethink within the department.

With as many as 70 devices occasionally being seized on the execution of a single search warrant, Lancashire’s digital detectives concluded that they were going to have become more discerning about how they cast their net in the hunt for the county’s tech-assisted criminals.

“Whilst we were giving each job an exceptional response, there were hundreds of others sat in a queue that we were not doing anything with,” Adam says.

“Now we take a more intelligence-led approach. So if we are looking for a device which is linked to indecent images being uploaded to the internet and we find an old Nokia phone in an attic, with no SIM card in it, then we may see if there are other avenues for checking whether that handset has been involved [rather than deploying the full suite of digital examination tools].”

The level of evidence required by the Crown Prosecution Service in order to bring charges is also now taken into consideration when determining the extent of the analysis which is carried out in some cases.

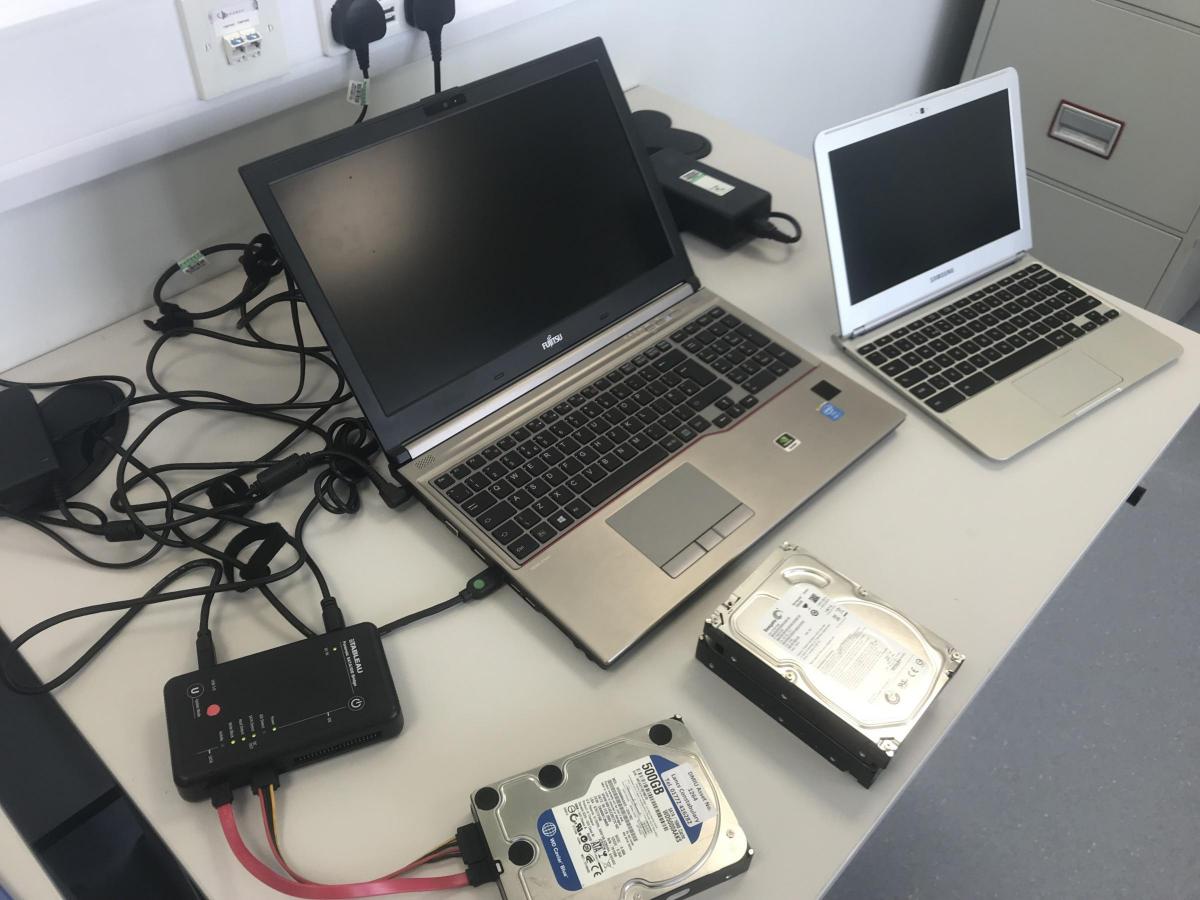

Meanwhile, the installation of ‘digital kiosks’ – machines which can carry out lower-level readings of devices at 13 sites across the county, including Preston and Blackpool – has helped ease the pressure on the main DMIU team at the force headquarters at Hutton. Hundreds of divisional officers have been trained in how to use the technology-scanning kit, but still have the option of referring complex cases to their more specialist colleagues.

The results of the revised approach have been stark – the maximum time for analysing the devices in a given case is now down to ten weeks. The most serious investigations continue to get a prioritised same-day service.

But there remain limits to the speed at which the department’s work can be undertaken.

“We are very often dictated to by how quickly or slowly a little blue line goes across a screen,” Tony explains.

“A court could require something in two days and we have to say it won’t be ready – but judges are relatively sympathetic to the fact that if they are asking for something which we say will take weeks, then there is no point in them insisting that it’s done in days.”

As criminals have become increasingly reliant on technology to commit crime, so too have the police found themselves routinely turning to technology in their search for evidence.

The DMIU is involved in most cases which Lancashire Police investigate, ranging from human trafficking and organised crime to murder and harassment. According to Adam, analysis of digital devices has “changed the DNA of policing”.

“There are cases now which make you wonder how convictions were made before we did this type of work.

“Years ago, you could walk around the streets and you wouldn’t leave much of a footprint, other than for some fuzzy CCTV.

“Now you’re carrying around a phone which is a GPS tracking device and has on it everything you’ve searched for – all your plans, saved and stored.

“In some ways it’s made things simpler, but in others it has added complexity and demand,” Adam says.

One aspect of that complexity has arisen from the investigative rigour required in processing the new mass of evidence which digital potentially provides.

Lancashire Police has recently had its work validated by the UK Accreditation Service, a standards organisation which assessed the way in which the DMIU operates. The status conferred on the department is just one of the ways in which police forces can demonstrate to the courts that their digital evidence can be relied upon.

“If we identify any major issues which could result in a miscarriage of justice, there is a responsibility on us to report that to the regulator,” Adam explains.

Tony adds: “We have quite a lot of interaction with the investigating officers and a role in the investigative process – we don’t just hand the data over and leave them to make their own judgements.

“We have to look at the evidential value of everything – the presence of something isn’t necessarily good evidence in itself. It’s the things around it, such as the opportunity for someone to have been committing the [crime] on that device.

“But we do rigorously retain our independence – we are as keen to find somebody in possession of something which proves their innocence as their guilt.”

Courts do not unquestionably accept digital evidence – and the DMIU team often have to explain and defend their work at trials. Sometimes that can prove more difficult than others – occasionally, for the most unexpected of reasons.

“I was giving evidence in court once and spoke about a folder on a computer,” Tony recalls.

“The judge stopped me and asked the jury if everybody knew what a folder was and this little old lady said she didn’t – so he had to explain to her by comparing it to the folder on his desk.”

But as policing increasingly shifts from an analogue to a digital world, comprehension problems like that will no doubt become increasingly rare.

The changing landscape has also seen the DMIU in Lancashire adopt a new motto – “Using digital for public good”.

Perhaps an understandable sentiment for a department confronted with the daily reality of the way digital can be deployed to the detriment of us all.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here