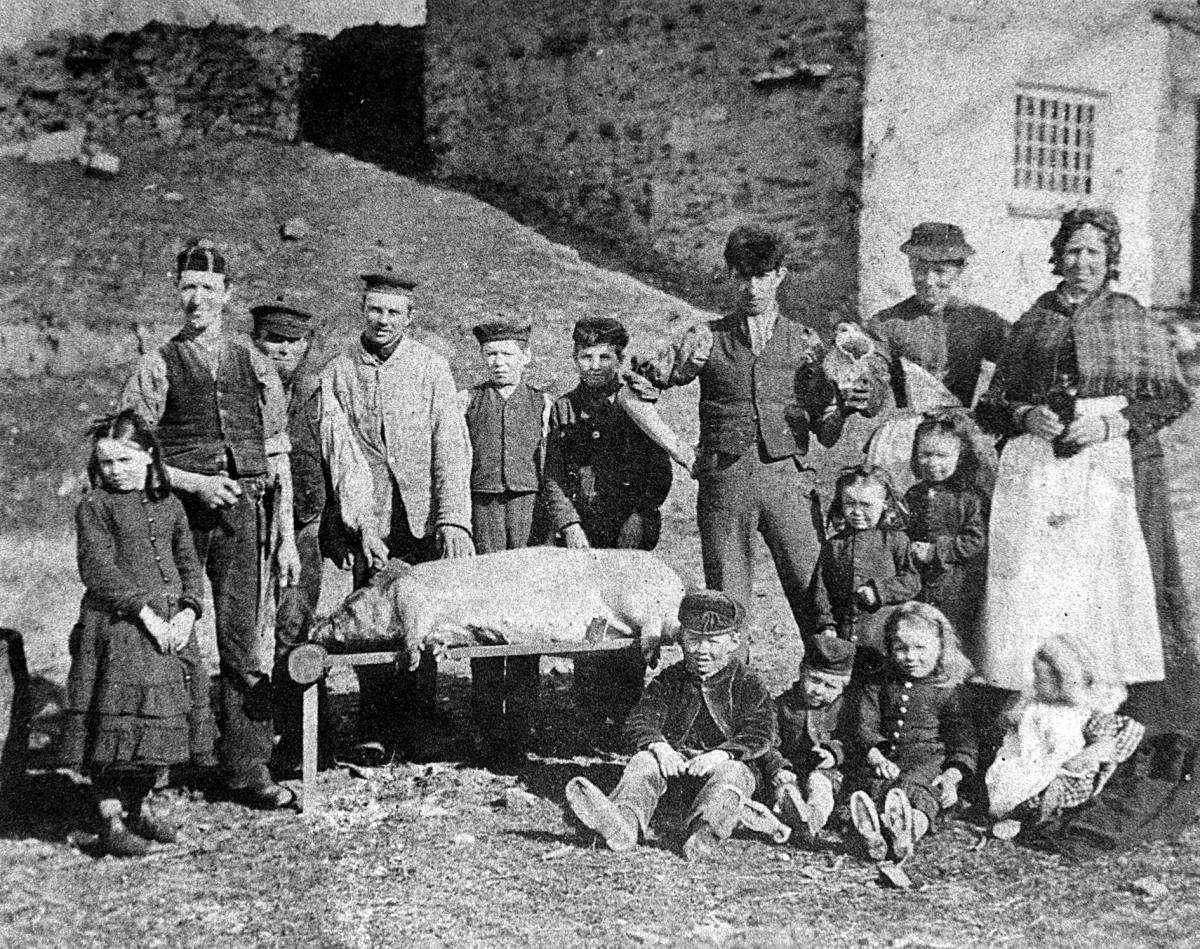

DAVID WILLACY recalls the day that the smallholding's 'house pig' was slaughtered during the war years

I WAS raised on a smallholding and attended the local primary school; wartime, 1939-45, evacuees galore, interesting years.

Almost all our village fathers were in the forces or on war-related duties. Food was rationed and we all had the dreaded ration books, but living in the countryside, we were very, very lucky. There was plenty of eggs, butter, homegrown vegetables, but lots of work for everyone.

The largest bonus was having a house pig, which was fed on any scraps or waste. It was usually a large white boar.

A day to remember was the killing of that poor pig. We all approached the pigsty with caution, trying to lasso it with a stout rope. It had to land behind the ears and under the chops. Then, leading it down towards the house, it just screamed and screamed; you could hear it miles away.

We had a special wooden bench which we called a pig creel. Then we had to get the pig on to it. After securing the pig with ropes we tied it so it couldn’t get off.

The man with the knife, who would come specially to help, did what he had to do, and I was standing by with a clean bucket to catch the blood. I had to stir it vigorously to stop it clotting and it was taken away to make black pudding.

The house washing-boiler, which had been stoked up early that morning, provided us with plenty of boiling water. The dead pig was loaded into a large tin bath and the boiling water poured over it. One or two people then scraped all the hair from the pig so it was then nice and clean. When this task was completed the carcass was hoisted up on end to a roof beam and split open from top to bottom.

The entrails were all separated and cleaned ready for making sausages. The heart, liver and kidneys were taken into the house and later, divided among friends because there were no fridges and it needed using while it was fresh. The butcher man took a pen and marked out the hams, shoulders and flitches, and then set about cutting it up.

By this time, I had retrieved the precious bladder which was blown up and the end sealed. It was then hung up from the wash house ceiling and left to dry out over several weeks. Because it was wartime, and there were no toys in the shops, this was a valued plaything. It was used for hand ball and rugby, mostly in the house so that it did not get damaged.

Indoors, the women were now busy mincing the meat for sausages, using the saved intestines as skins. A small machine was on hand to fill the sausages, which were hand-knotted and the same with the black puddings.

The hams, shoulders and flitches were laid out on a shelf and covered with saltpetre to cure it for a period. Pieces of pork were distributed to friends and neighbours as gifts, which was reciprocated when they killed their pig. There was a lot of food for a short period. It was a feast, then famine.

I remember the old workmen from Kendal taking a pigs’ trotter for their work lunch; there was an old saying “you can eat all the pig except for its squeak”.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel