Wakes Week holidays became a tradition in northern towns following the Industrial Revolution, so the cotton mills and manufacturing factories could be closed for maintenance.

From June to September a different town was on holiday each week — though the workers were not paid.

While an agreement for 12 days annual holiday was finally reached in 1907, which increased to 15 days in 1915, it wasn’t until the 1940s and 50s that paid holidays became reality.

Indeed, back in early Victorian times mill workers were lucky to have Sunday off – to attend church – and holidays were unheard of.

Just 50 years before the turn of the century it was reported that Darwen workers ‘warmly expressed their thanks’ to the town’s principal employers because their annual holiday had been extended from one to two days.

There was a long-held belief among the mill workers of East Lancashire that bathing during the summer was ‘physic in the sea’ and the expansion of the railway network led Blackpool to become a resort catering mainly for the Lancashire working classes.

The resort enjoyed a peak year in 1860 as thousands of holidaymakers flocked there, and in the last quarter of the 19th century trips increased from day trips to full weeks away.

To help pay for their holidays, workers would make regular payments into Wakes Saving or Going-Off clubs during the year.

With the opening of new lines and new stations, Blackpool steadily established itself as the Kingpin of the Coast.

The railways brought an era of rapid expansion – and hundreds of thousands of Wakes Weeks holidaymakers from East Lancashire.

With the development of the North Pier, which had opened in 1863 and two more, together with the building of the promenade, the stage was set.

Hotels, lodging houses and theatres sprang up everywhere.

Blackpool Pleasure Beach, once described as ‘an unpretentious fairground at South Shore’, was expanding steadily into one of the country’s giant amusement parks.

Blackpool Tower opened in 1894 to, almost literally, put the tin hat on the now thriving town and there was a giant ferris wheel close to the Winter Gardens.

It’s probably not easy now, more than 100 years on, to imagine just what an attraction it all was to the mill workers of industrial Lancashire.

Thanks to rail travel, it was virtually on their doorstep.

Of course, as the years progressed, holidaymakers travelled further afield for their July summer holidays, and seaside specials ran from local stations to all points north, south, east and west, while bus companies also added holiday coaches to the timetable to take passengers to the coast.

In 1953, 36 specials left Colne station on the first day of the holidays and in Burnley there was a wedding rush as couples combined honeymoons with holidays to Rhyl, Morecambe and the Isle of Man. Fifteen were scheduled at the register office before 1pm and the registrar and his deputy had to work a double shift.

In 1968 hundreds of Accrington holidaymakers were delayed an hour after vandals smashed several coach windows on the 07.19am to Llandudno.

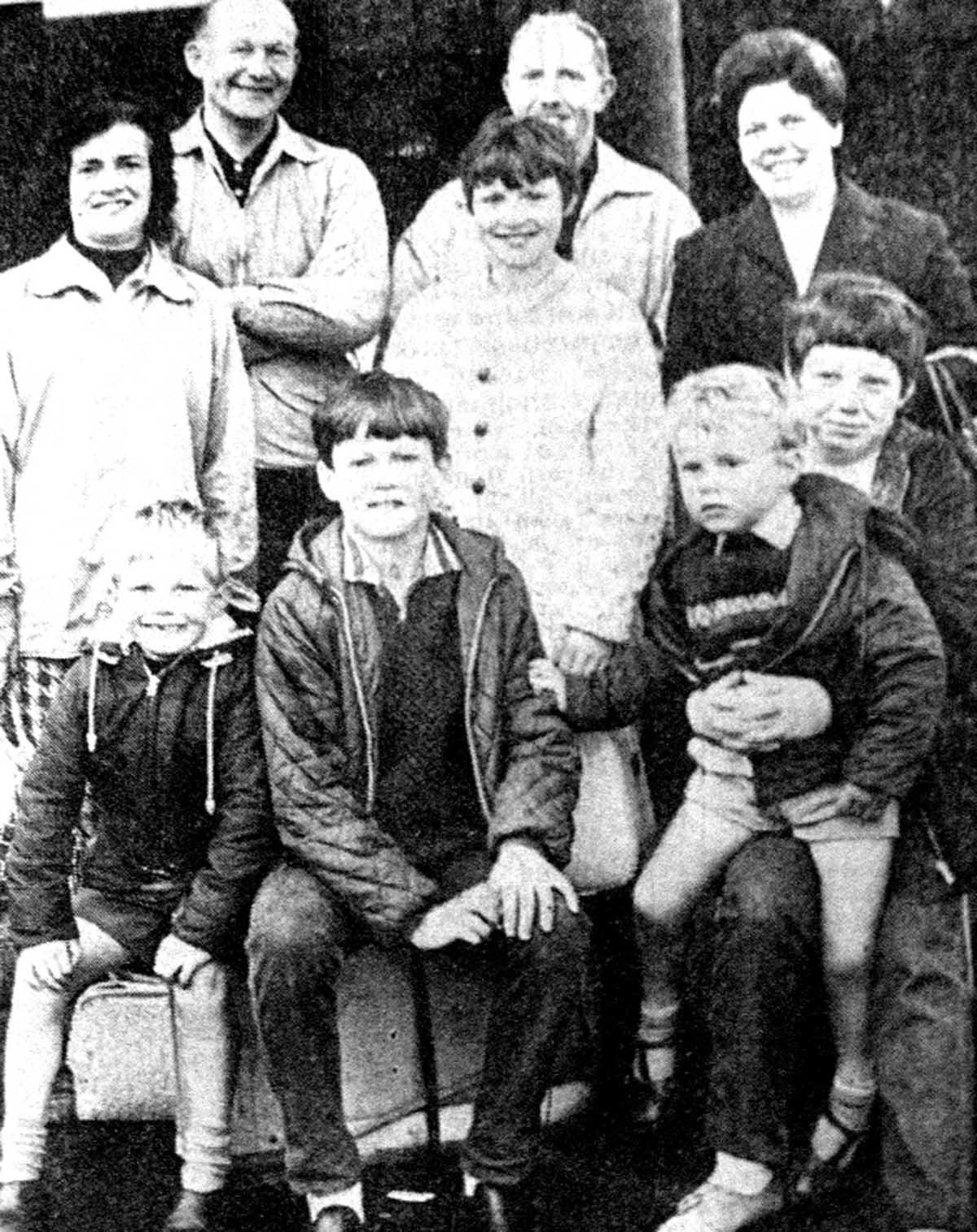

Among the passengers on board the nine-coach diesel were Arthur and Irene Saunders of Burnley Road and their children Sarah, Stephen, Andrew and Simon, pictured top, left, with another family on the platform.

n The Fylde Coast features in a new multi-sensory, hands-on exhibition at Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery, titled Beside the Sea.

It celebrates the popularity of seaside trips in the late-Victorian and Edwardian eras to places like Blackpool and looks at the seaside as a great source of relief from hard working lives. Entry is free and the exhibition runs until September 21.

One exhibit is a pastel of Arnside on Morecambe Bay by Darwen artist James Hargreaves Morton, who was killed at the close of the Great War.

An exhibition of original Morton paintings and pastels is on at Darwen Library till mid-August. It includes several works which had never been seen in public.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here